Mennonite Health Journal

Articles on the intersection of faith and health

Mennonite Health Journal, Vol. 19, No. 10, June 4, 2018 PDF

Student Elective Term (SET) Report

Jenna Nofziger, MD

March 24 – May 6, 2018 in Shirati, Tanzania

If medical school has taught me anything-which, as someone receiving their medical license shortly, I hope it has-it’s to take this work one day at a time. The inundation of study material, clinical experiences, and hoops to jump through calls for breaking up responsibilities into manageable pieces. Processing experiences after the fact, so as not to get bogged down by worry and stress, has become a defense mechanism for me over the last four years. Do I think this is always the right way, or do I wish I had a little more capacity to plan for experiences like SET without succumbing to fear of the unknown? Absolutely! However, this is where I am at right now on the journey to accept that God has everything in control and never gives me more than I can bear.

To say that I went into my SET experience at Shirati KMT (Kanisa la Mennonite Tanzania) Hospital in Shirati, Tanzania blindly would not be too much of an overstatement. The month of March was occupied with the ever-present question, “Where did I match?” On March 16, I opened an envelope telling me where I would spend the next three to four years of my Emergency Medicine residency. The following Saturday, I headed off to Tanzania to spend four weeks in a foreign hospital. The only words I knew to communicate with patients came from watching Disney’s The Lion King as a child. Where was that wise old baboon Rafiki when I needed guidance?

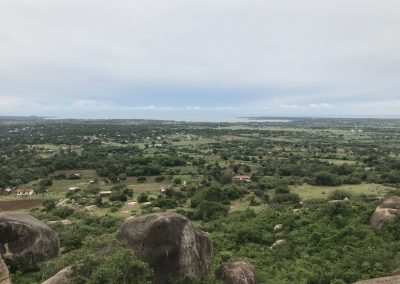

Shirati KMT Hospital is one of two hospitals in the Tarime district of the Mara region in northern Tanzania. It sits next to the beautiful shores of Lake Victoria, which is a source of fish, fertile soil, water for people and livestock–as well as schistosomiasis, the result of a gastrointestinal parasite that causes diarrhea in the short term and liver cirrhosis and bladder cancer in the long term. The hospital has grown from the few huts dedicated to medical care to a sprawling campus with 150 beds, which hold multiple people at the busiest of times. The services offered at this rural establishment are quite impressive, including separate wards for female, male, maternity, and pediatric patients; operating theatre, physiotherapy, palliative care, laboratory, radiography and ultrasound, outpatient care, HIV/AIDS clinics; as well as women’s and children’s clinics.

Thanks to the work of hospital staff and other area NGOs (non-governmental organizations), the rate of HIV/AIDS in the area has decreased from around 13 percent to 6-7 percent of the population. But this commendable fact does not make the staff complacent. Specialists are frequently brought into the hospital for services otherwise unavailable to most patients. One can hear about these opportunities from announcements at the Mennonite church or by listening to the truck driving through the streets of Shirati, which blares the news from a loud speaker. In the short time I was there, eye, bone and joint and plastic surgery specialists came to donate their time and skills to the people of Shirati. Cleft lip and palates were made whole, and severely deformed knee joints due to malnutrition in childhood were straightened. Patients of all ages were given new hope and futures were rewritten.

I went into my term with little to no expectations and minimal framework for how I wanted to spend my time there. When I arrived, the hospital’s director, with whom I had set up my arrangements, was travelling for a conference, and no one was exactly sure when he would return. Harnessing my wisdom from four years in medical school, I went with the flow. The day I started, I was told to fill in for the physician who typically rounds in the female ward. There were clinical officers, similar to physician assistants, and others around the hospital that I could reach out to if I needed help, but they each had their own ward and patients to oversee. Two hours later, after standing around the ward asking nurses if they would help me round (I needed translation from English to Swahili) I began. I was on my second patient out of about 17 when I encountered an especially difficult situation.

A 16-year-old with suspected diabetic ketoacidosis, DKA, began vomiting a coffee-ground emesis. DKA is a serious condition where the body of a diabetic begins breaking down fat at a higher than normal rate into acids called ketones. It is life-threatening, even in the United States, but profoundly treatable with the correct treatment and monitoring. I ran to the patient’s bedside, encouraged the family that surrounded her to help turn her on her side, and began checking vital signs. She was unresponsive, tachycardic, and hypotensive. A minute later, she was not breathing and had no pulse. I stood there helplessly without basic medical equipment: no EKG, no oxygen, and no acute cardiac life support medications. I tried to initiate CPR while the few nursing students around me looked on. There was nothing I could do. The family was wailing, nurses were going about their usual work, and I stood by the body of a 16-year-old girl who under different circumstances wouldn’t have died, but did.

Two days later, I had a similar experience with a girl far too young and sick to be saved. As I began to process these cases, I realized that I needed to set a framework for myself to shape the way I experienced Shirati. I could not take one day at a time, because that would not defend me from the heartbreak of powerlessness and helplessness that comes with watching patients die of causes whose treatments I learned in medical school.

Four weeks is a short time to establish relationships, gain trust, learn routines, and develop a rhythm, made even more difficult with a language barrier. My goal became, simply, to experience. I was not there to help, to make a difference, or to implement change–although, I hope I did some of that. I was there to learn how professionals in an understaffed and under-resourced hospital were doing what they could for the people of the region. I learned that public health measures, not acute care, was the best way to utilize resources and save lives.

Outside of hospital work, I also had the pleasure of participating in outreach trips with various hospital-based clinics. This consisted of loading everything needed for the day, basically the whole clinic, and a small team in the back of a truck. The team would then go out to surrounding villages 10-40 minutes away from the hospital and see as many patients as came. Events included cervical cancer screening, an HIV/AIDS clinic, and women’s and children’s clinics. At these villages I saw the injustice of children not in school because they were sent to collect HIV/AIDS medications for family members. I saw fear as I performed first-time pelvic exams on women 30 years and up. I saw hope in babies hanging in jumpers from a spring and hook scale in a mud brick building. I saw love in the eyes of staff counseling mothers on nutrition practices, telling women they were cervical cancer free, and laughing with patients who were going to live another month.

As I approach my residency training in Emergency Medicine, this trip was a reminder to appreciate the medications and equipment at my disposal. I already knew that being a physician is a privilege. However, being a physician and having the resources to do your job in order to heal those in critical need is a privilege less highlighted in the U.S. medical school curriculum. I hope I remember to say a prayer of thanks each day I am able to put on a pair of examination gloves.

About the author

Jenna Nofziger, MD, received her MD degree with the Class of 2018 from University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences in Toledo, Ohio. Jenna is a 2014 graduate of Goshen College and is married to Nathaniel Klink. She will be starting her medical career as an emergency medicine resident with Washington University at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri. In her free time Jenna enjoys exercise, reading, spending time with family, and lake activities. Jenna is a member of Zion Mennonite Church in Archbold, Ohio.

Jenna Nofziger, MD, received her MD degree with the Class of 2018 from University of Toledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences in Toledo, Ohio. Jenna is a 2014 graduate of Goshen College and is married to Nathaniel Klink. She will be starting her medical career as an emergency medicine resident with Washington University at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri. In her free time Jenna enjoys exercise, reading, spending time with family, and lake activities. Jenna is a member of Zion Mennonite Church in Archbold, Ohio.

Photo Gallery

Female Ward

Female Ward at Shirati KMT with areas for medical and surgical female patients. On average 15-20 women are in the ward at all times.

Cancer screening

Set up from the cervical cancer screening outreach program. The program also provides cryotherapy for treating small, possibly pre-cancerous lesions on site.

Rainbow

A rainbow appeared over the Male Ward of the hospital after a particularly trying, yet satisfying day.

Outpatient Department

The outpatient department, staffed 24 hours by clinical officers. Patients are evaluated here first, given lab orders, and admitted for care or discharged for home treatment.