Mennonite Health Journal

Articles on the intersection of faith and health

Mennonite Health Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3, July 6, 2020.

Student Elective Term Report

Gulu Regional Referral Hospital, Uganda

February 1 – February 29

Jesse Voth-Gaeddert

This last February I did a 4th year medical student rotation in Gulu, Uganda with the support of Mennonite Healthcare Fellowship. I worked at the Gulu Regional Referral Hospital (GRRH). in northern Uganda. With the goal of loving thy neighbor as thyself, I hoped to further explore international work as an expression of my faith.

Additionally, I sought out this four-week rotation to deepen my understanding of how physicians use their specific skill set to serve those in a culturally diverse and resource-limited setting. I also hoped to learn how culture impacts the intricacies of providing health care and how I could navigate through these differences.

Additionally, I sought out this four-week rotation to deepen my understanding of how physicians use their specific skill set to serve those in a culturally diverse and resource-limited setting. I also hoped to learn how culture impacts the intricacies of providing health care and how I could navigate through these differences.

GRRH is a publicly funded hospital that has many hospital departments similar to what you would see at a US hospital (Inpatient Wards, Obstetrics/Gynecology, Pediatrics, Ophthalmology, ect.). However, this may be where the similarities end. While US hospitals have seemingly endless resources, GRRH seemed to have hardly any resources at all. We had to be very conscientious and intentional about using items that I had always taken for granted, like exam gloves, cotton ball swabs, or sterilization agents. Instead of Electronic Medical Records (EMR) they used notebooks which were often difficult to read, unorganized, and sometimes misplaced. There was only one bottle of hand sanitizer provided on the men’s and women’s wards and it was watered down to last longer, which was especially concerning given the oncoming pandemic. Furthermore, sick patients lay in hot and humid buildings with windows and doors open to the outside. Thus, seeing mice and wasps inside buildings was not uncommon.

I spent most of my time in adult inpatient  rounding with Ugandan doctors and medical students as well as a volunteer doctor from Canada. Since medical students help with nursing work, I would occasionally draw blood and help start IV’s along with typical medical student tasks like patient histories and physical exams.

rounding with Ugandan doctors and medical students as well as a volunteer doctor from Canada. Since medical students help with nursing work, I would occasionally draw blood and help start IV’s along with typical medical student tasks like patient histories and physical exams.

Along with adult inpatient, I also spent time helping at the hypertension clinic. Because the hospital had no hypertension medications delivered the previous month from Kampala, Uganda’s capital city, many patients had concerningly high blood pressures. To make sure we were not prescribing out-of-stock medications, we started checking the pharmacy before clinic to see what medications they had in stock. And even if we were in stock, patients and their families sometimes did not have the money to pay for needed medications or labs, which is paid for out-of-pocket. Many Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) patients I saw in SCD clinic could not afford to regularly check their blood counts, which is important to track progression of SCD. This made their clinical presentation and physical exam especially important. Additionally, clean drinking water is not readily available in villages, making it difficult for SCD patients to stay adequately hydrated, which is important to prevent acute crises caused by sickled red blood cells. Furthermore, diagnostic capabilities were limited at the hospital. X-rays and ultrasound were the extent of imaging, and the X-rays were read by hand, held up to light. Occasionally, imaging would not be available at all because of the power going out.

Along with limited resources was the challenge of communication, which is partly credited to Uganda’s history of violence. A Ugandan medical student explained to me that Uganda, especially the surrounding Gulu area, has many tribal languages spoken in the villages. To know English, villagers must have attended school. Due to the recent history of violence in northern Uganda caused by the Lord’s Resistance Army (aka Kony’s Army), many never attended school, and, thus, did not learn English. The lack of English proficiency and the many different tribal languages can make it difficult to find someone to translate for patients. From my experience, some patients often had a family member who knew English and could translate for us, but sometimes we had to ask around and see if anyone could translate. Occasionally, family of other patients or even other patients themselves would translate for us. While patient privacy is mandated under the Ugandan Constitution, this was not as strictly enforced in Gulu.

Along with limited resources was the challenge of communication, which is partly credited to Uganda’s history of violence. A Ugandan medical student explained to me that Uganda, especially the surrounding Gulu area, has many tribal languages spoken in the villages. To know English, villagers must have attended school. Due to the recent history of violence in northern Uganda caused by the Lord’s Resistance Army (aka Kony’s Army), many never attended school, and, thus, did not learn English. The lack of English proficiency and the many different tribal languages can make it difficult to find someone to translate for patients. From my experience, some patients often had a family member who knew English and could translate for us, but sometimes we had to ask around and see if anyone could translate. Occasionally, family of other patients or even other patients themselves would translate for us. While patient privacy is mandated under the Ugandan Constitution, this was not as strictly enforced in Gulu.

Rotating abroad did not come without its personal challenges. There were times when I found myself hyperaware of the hot and sticky weather, the lack of air conditioning, and the scarcity of internet. We also had to navigate what foods were safe to eat, remember to wear sunscreen because of our malaria medication’s sun-sensitivity side-effect, and we stuck out like a sore thumb due to our difference in skin color and my difference in height (6’4”). Too, I found it near impossible to escape the presence of bugs. Even sleeping under a mosquito net, I woke up one night to the sound of a mosquito buzzing at my ear and rolling over to see a fat and happy tic waddling away from my pillow. All things the locals probably expected would “bug” a privileged white foreigner like me.

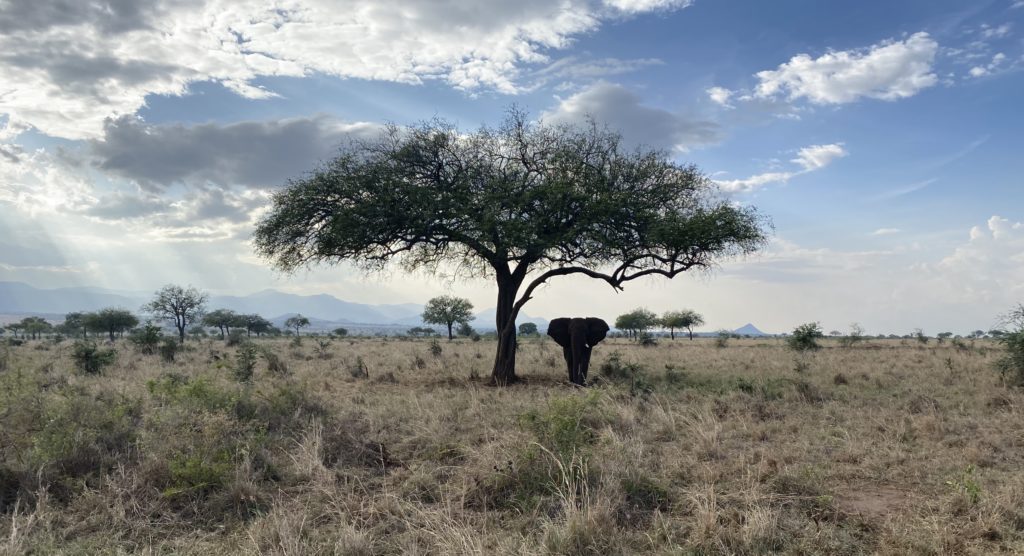

Nonetheless, inside and outside of the hospital my classmates and I found Uganda to be filled with kind-hearted and welcoming people, with a backdrop of beautiful wildlife. Us mzungus (white persons) were fortunate enough to form friendships with locals, enjoy Ugandan cuisine, and see some of the unique Ugandan wildlife. One highlight of my time in Uganda was  attending Catholic mass. We got to hear beautiful Ugandan voices singing in a large, packed Catholic church. We also attended an Ash Wednesday service and received ashes with fellow churchgoers. One particular service, the priest spoke about the Sermon on the Mount and reminded us all of the need to care for each other, especially those who are most in need. The opportunity to worship and receive ashes alongside hundreds of Ugandan men, women, and children, punctuated my time in Uganda and is one experience I will not forget.

attending Catholic mass. We got to hear beautiful Ugandan voices singing in a large, packed Catholic church. We also attended an Ash Wednesday service and received ashes with fellow churchgoers. One particular service, the priest spoke about the Sermon on the Mount and reminded us all of the need to care for each other, especially those who are most in need. The opportunity to worship and receive ashes alongside hundreds of Ugandan men, women, and children, punctuated my time in Uganda and is one experience I will not forget.

In hindsight, I see how lucky I was to have had this medical rotation in February and not a month later given the current pandemic. I am extremely grateful for the support Mennonite Healthcare Fellowship provided me in this endeavor. This experience has given me an idea of what I would and would not want my future international work to look like and deepened my understanding of how to navigate limited resources in a unique health care culture. As I advance in my medical training, international service will remain in the back of my mind as one avenue to express my love for God and God’s love to others. I would encourage all my fellow health care workers and trainees to do the same.

About the author

Jesse Voth-Gaeddert was a fourth-year medical student at the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita in Wichita, KS when he did his SET in Uganda. Originally from Hesston, Kansas, Jesse graduated from Bethel College, North Newton, KS in 2015 and then served a year with Mennonite Central Committee’s Serving And Learning Together (SALT) program in Hanoi, Vietnam. Jesse graduated from medical school in May of 2020 and is now a Family Medicine Resident in Grand Junction, CO.

Jesse Voth-Gaeddert was a fourth-year medical student at the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita in Wichita, KS when he did his SET in Uganda. Originally from Hesston, Kansas, Jesse graduated from Bethel College, North Newton, KS in 2015 and then served a year with Mennonite Central Committee’s Serving And Learning Together (SALT) program in Hanoi, Vietnam. Jesse graduated from medical school in May of 2020 and is now a Family Medicine Resident in Grand Junction, CO.