Emmett, Aamir, and our Interconnectedness

A Sermon on Firearm Violence

Emmett Till, Aamir, And Our Interconnectedness

A sermon delivered at Germantown Mennonite Church, June 2022 – Cate Michelle Beaulieu-Desjardins

Scripture:

1 Corinthians 12: 12-27

Just as a body, though one, has many parts, but all its many parts form one body, so it is with Christ. For we were all baptized by[a] one Spirit so as to form one body—whether Jews or Gentiles, slave or free—and we were all given the one Spirit to drink.

Even so the body is not made up of one part but of many. Now if the foot should say, “Because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason stop being part of the body. And if the ear should say, “Because I am not an eye, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason stop being part of the body. If the whole body were an eye, where would the sense of hearing be? If the whole body were an ear, where would the sense of smell be?

But in fact God has placed the parts in the body, every one of them, just as he wanted them to be. If they were all one part, where would the body be? As it is, there are many parts, but one body. The eye cannot say to the hand, “I don’t need you!” And the head cannot say to the feet, “I don’t need you!” On the contrary, those parts of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable, and the parts that we think are less honorable we treat with special honor. And the parts that are unpresentable are treated with special modesty, while our presentable parts need no special treatment.

But God has put the body together, giving greater honor to the parts that lacked it, so that there should be no division in the body, but that its parts should have equal concern for each other.

If one part suffers, every part suffers with it; if one part is honored, every part rejoices with it. Now you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it.

A few years ago my partner and I eagerly awaited the opening of the new National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington D.C. At the time, tickets were released one morning every month and snapped up within minutes. We got up very early one day and were excited to be assigned two tickets at a random timeslot in late Summer. We flew to DC and couldn’t wait to see the new museum – although I’ll admit I hadn’t read as much about it as my partner had.

The museum is designed from the bottom – up: you take an elevator “through time” down to the dawn of enslavement and work your way up through spiraling floors toward present-day history. Somewhere about 1/2 ways up, we encountered a very long line.

We have a rule when traveling: sometimes a line means there’s something good at the end, and being a British-American couple, queuing up is definitely one of our strong points. So we got in the line, not bothering to ask around what it was for. As the line wound around and around, we started to hear mournful music, and then – almost surprisingly – a casket came into view.

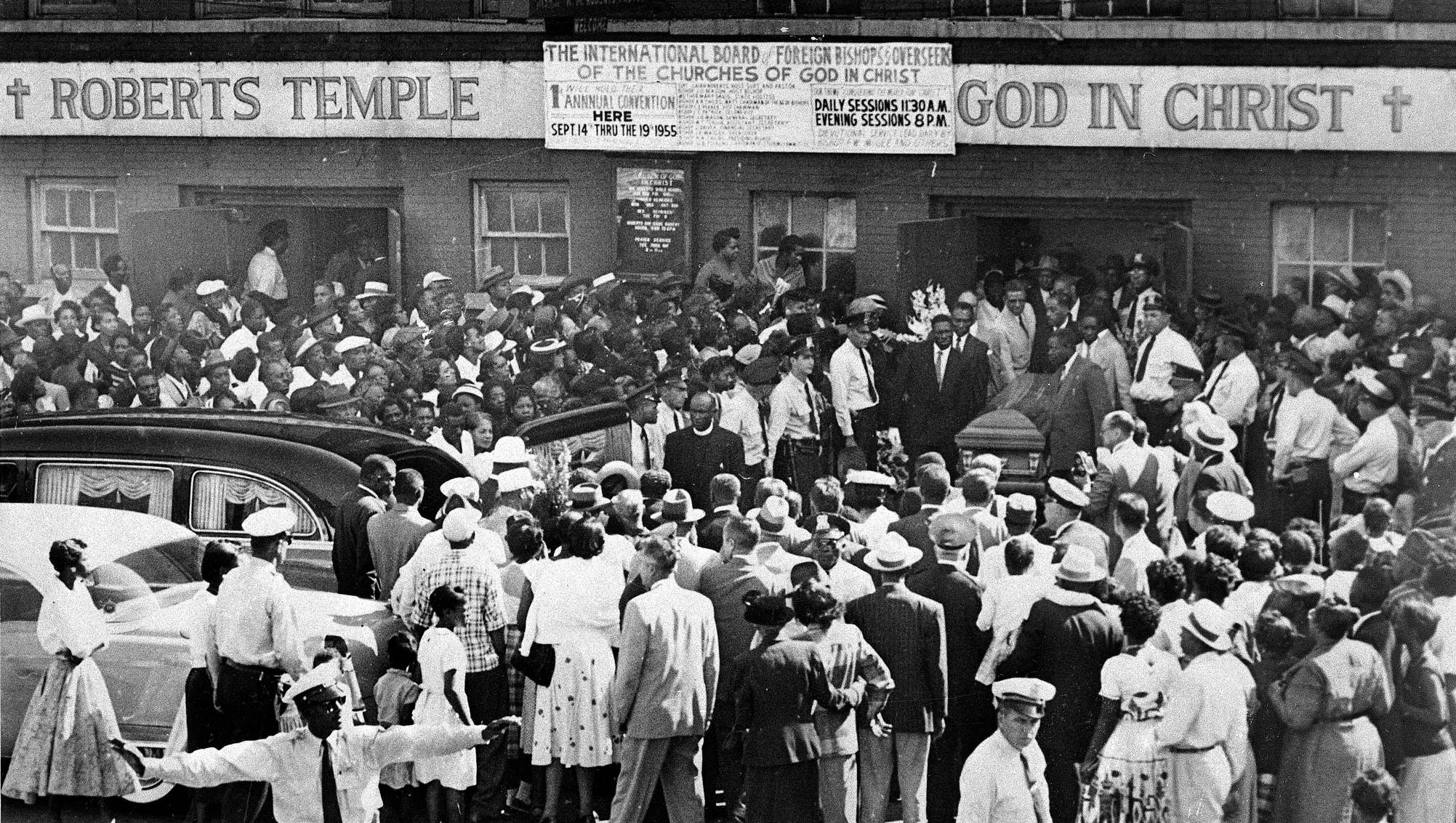

It was Emmett Till’s original casket, given to the Smithsonian after being tossed aside in a shed after Emmett had to be exhumed to “prove it was him” as a part of the ever-ongoing investigation into his brutal murder. We stayed in the line, rounded the corner, and, as the exhibit is designed for, peered down into a glass-covered photograph of his body- his grotesquely mutilated face – placed just like it was when his mother courageously chose that the world needed to see “just what they’d done” to Emmett and held his viewing and funeral with an open casket.

Just a month or so earlier I walked briskly down a hospital corridor. I was on one of my least-favorite 24-hour weekend shifts at the hospital. The pager had gone off. That, of course, wasn’t unusual. To see a Trauma STAT, our highest triage level at 12 noon was unusual. The page read simple, GSW, 5 y.o. GSW stands for Gun Shot Wound. We waited and waited in the trauma bay, every doctor and team imaginable. Let’s just say that waiting that long is rarely if ever good. When he arrived, it became immediately clear he had been shot in the face and there was very little that could be done. I won’t describe to you in detail what I saw that day, but I will tell you that it is simultaneously something I will never, ever forget, and something my resilient brain – in protecting me – tries really hard to make me forget. I will also tell you that while his body was indescribable, there is one detail that stands out. It was a hot July day, and like many little kids, his family had set up the sprinkler outside to help him cool off. The clothes he wore as he was shot and later died were tiny little spider-man swim trunks.

I said I wouldn’t describe that little boy’s injuries, but I will tell you that just months later, when I looked down at the photograph of Emmett Till’s face, the first thought I had was: I’ve seen that face before. I had seen a face that looked that…indescribably horrific…just months before. Another Black boy. The violence that killed that five-year-old was not the same brutal racist violence that killed Emmett. No. On the day he was brought in everyone was convinced he somehow got ahold of a firearm and accidentally set it off himself. Months later we learned it was his sibling, another child, picking it up out of curiosity. There is actually a lot more to that side of the story, and that first day in the trauma bay was not, by far, my last encounter with the family, but of course, this is where HIPPA – our patient protection laws – come into force, laws I both love and deeply wrestle with. And wrestled with more that day after seeing Emmett. Because when I really think about it, while we hear so often on the news about these horrific events, there are very few people in the world that truly know, visually and viscerally, what firearms do to children. There was a haunting if cagey NPR article about Uvdale from the medical examiner who would not describe what he saw. Instead, he said, “It’s something you never want to see and it’s something you don’t, you cannot prepare for. It’s a picture that’s going to stay in my head forever, and that’s where I’d like for it to stay.” As always, as healthcare providers, medical examiners, or parents, we only share in parts and metaphors and halves. And part of me understands that. Self-care is important, it’s hard enough to even watch the news, and privacy is important and all of those things. Yet part of me thinks sometimes: but if people had just seen what I’ve seen, or heard the fullness of this story…would this whole situation we are in as a country, this epidemic, this horrific, terrifying, gruesome, inequitable violence be stopped by now? Of course, I’m not standing here before you as some illustrious activist out every day protesting and working to end firearm violence. Sometimes seeing what I’ve seen is also paralyzing and overwhelming. Yet I do think it asks of me, that little boy asks of me, to try my best, to try to tell, to try to hold – which, I suppose, is what I’m doing this morning.

For me, these two stories will forever be interconnected – Emmett Till, and a little boy whose name I desperately wish I could speak to you, whose name in so many ways shouldn’t be a secret, should be remembered, but who for now I’ll call Aamir.

And I think I’m not alone in having had a profound moment or moments of Deja Vu related to firearm violence. In twisted ways on the news it’s like we are seeing Emmett and Aamir’s faces, violence repeated, too eerily similar again, and again, and again, and again.

One of the things I love about Jesus in all of his miracle and encounter stories is simply this: when someone came to him in pain with a broken body (let’s not forget how disfigured leprosy can render a person), or broken mind (the demoniac in Mark) – Jesus did not look away. I know that in these cycles of violence on the news my temptation is to look away. I know that at the moment I was asked to lay my hands on Aamir’s body after they called the time of death and pray over him, it would have been easier for me to murmur words while looking away from his face, his tiny hands, those small swim trunks. But I didn’t, and I hope that’s one tiny mite of dignity returned to him.

One of my practices right now is to not stop walking by Andrew’s house, the neighbor of ours killed in his driveway last year, and when I do, to not do what my instincts say which is to stare across the street, shuffle past, get out of there. Instead to keep the gentle pace my aging dog prefers, to let him sniff the hedges where Andrew’s impressively well-behaved dog, Ruckus, used to stand without a fence and calmly watch us walk by, and while I do so try to pray: for Andrew’s family who still has no answers, for Ruckus, for his killer – we don’t know who or why or how, but I can say I know that person is suffering, deeply, to have done something like that. To not look away. Mamie Till Mosely is one of my heroes, because she asked the world to not look away, and today, 67 years after Emmett was murdered, there are people lining up, waiting for nearly an hour, to look and see him, to not look away. And we know from the historical record, that her act of asking us to see the brutal realities of racialized violence has made a profound impact on the movement for Civil Rights here in America. I think bearing witness is a profound spiritual practice. It is, at times, difficult for me. It doesn’t feel like doing much, and I do believe now is a moment in our world, our city, and our congregation, where we need to envision together what we are going to do about firearm violence. Yet until we can also hold ourselves still and look and see, as Jesus did, all our doing may be futile.

Our scripture today from first Corinthians reminds us of our need for one another and our profound interconnectedness, like the unexpected interconnectedness of Emmett and Aamir, the ways we are woven together are many and mighty. Paul emphasizes this so beautifully in Corinthians: We are one body. When one suffers, we all suffer. This isn’t really a point I need to drive home – for I think it’s been driven home again and again in the last months. Indeed, our body, the body of this world, is suffering. And we feel it. The challenge I want to bring to us is to find healthy ways, within the practices of self-care that we do need, to be like Jesus in not swinging our necks around and looking away, but instead bearing witness. And I think in my healthiest moments of being able to bear witness without feeling completely activated and panicked inside, I am able to turn that witness into prayer. Sometimes those prayers are articulate, but that’s the rarity, most of the time they are just…a mix of random words and wondering and hopes and desperation. Sometimes I don’t even have words, but I can feel my body praying as I watch – whether that’s in the ER or violence unfolding on the news. And over time I’ve come to believe one part of bearing witness is telling stories, is telling the stories of the individuals that we need to hear. Of honoring our own stories, the things in our lives we need to bear witness to. Like the body, Paul describes, our own bodies and our own stories are interconnected and interdependent and warrant bearing witness to. Telling, Hearing, Holding.

Just a year or so after Aamir’s death and seeing Emmett Till’s coffin, I attended the semi-annual Faith and Writing conference at Calvin College in Michigan. Pádraig O Tuama was there and he read a poem that brought me right back to those days with Emmett and Aamir, which reminds me to bear witness to each life – whether killed in the period known as the Troubles in Northern Ireland, or in Cincinnati, or Philadelphia, or Alabama. It’s called “The Pedagogy of Conflict”.

…

When I was a child,

I learnt to count to five

one, two, three, four, five.

but these days, I’ve been counting lives, so I count

one life

one life

one life

one life

one life

because each time

is the first time

that that life

has been taken.

…

Hear Pádraig Read the whole of his poem here.

Read more about how Emmett Till’s casket came to the Smithsonian here.