Mennonite Health Journal

Articles on the intersection of faith and health

Mungindu: A poor but thriving community in Congo

Murray Nickel

from Mennonite Health Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3 – August 2013

We all know that that the Congolese lack a lot of things–adequate healthcare, effective education, a promising economy, sufficient infrastructure, even reliable peace. It doesn’t take years of study to recognize the needs in Congo. Poverty stares you in the face the moment you get off the plane. Since I graduated from medical school I’ve been asking the question, “What do the poor need?” Is it money or resources? Or is it skills? Probably. But none of these things seem to leave a lasting effect. It has dawned on me that the question I’ve been asking is all wrong. Let me explain.

Last November, I met briefly with Jean-Pierre, a school headmaster and supervisor of about sixty Mennonite schools in the area. I remember it clearly. We stood outside conversing, struggling to catch some shade from the burning Congolese sun. It wasn’t a long conversation. He asked me what it would take to get a teacher’s conference organized. I was fairly blunt. Organizing an event like that would be Jean-Pierre’s dilemma, not mine.

Last November, I met briefly with Jean-Pierre, a school headmaster and supervisor of about sixty Mennonite schools in the area. I remember it clearly. We stood outside conversing, struggling to catch some shade from the burning Congolese sun. It wasn’t a long conversation. He asked me what it would take to get a teacher’s conference organized. I was fairly blunt. Organizing an event like that would be Jean-Pierre’s dilemma, not mine.  But I did have a teacher friend, Mike, that I thought might be interested in raising a little money and possibly coming out next March. Jean-Pierre pressed further saying they had no resource books for teachers. I responded that maybe Mike could find a few books. But where would they keep them? They’d need a building to protect them.

But I did have a teacher friend, Mike, that I thought might be interested in raising a little money and possibly coming out next March. Jean-Pierre pressed further saying they had no resource books for teachers. I responded that maybe Mike could find a few books. But where would they keep them? They’d need a building to protect them.

That was it, a brief conversation. Four months later I found myself walking through the countryside to Mungindu with Mike, Jean-Pierre, and a few others.

Traveling in Congo is painful, slow and expensive. Interior roads, if you can call them that, are no more than long lines of chewed up sand and mud haphazardly laid through the grasslands and cut through the forests to connect one village to another. Deep ruts and washouts make descending into valleys a navigating challenge to avoid tipping over. Breakdowns are common. Sure enough, an hour later, twenty kilometers into the trip, we joined the statistics of broken down vehicles on the road. The back wheel had come off. So we picked up our packs and started to walk.

Traveling in Congo is painful, slow and expensive. Interior roads, if you can call them that, are no more than long lines of chewed up sand and mud haphazardly laid through the grasslands and cut through the forests to connect one village to another. Deep ruts and washouts make descending into valleys a navigating challenge to avoid tipping over. Breakdowns are common. Sure enough, an hour later, twenty kilometers into the trip, we joined the statistics of broken down vehicles on the road. The back wheel had come off. So we picked up our packs and started to walk.

Walking in rural Congo is nothing like driving. It’s slower, no doubt, but it also provided us opportunities we wouldn’t have had otherwise. We may feel alone in a vehicle, but we didn’t when we were walking. We passed numerous bicycles rigged with draw-strings guidance system and laden with sacks of manioc being pushed through the sand to market. Glistening with sweat, the bikers took time to be friendly, offering a brief greeting between puffs. We also get much wetter walking in Congo. If it’s not the sweat, then it will be the torrential rain. However, in Congo, rain can be most refreshing. The darkness settles in quickly making it hard to see. Yet that too forced us to stop and visit with the people that we meet. When we walked, we found that village people, wherever we went, fed us and offered a place to sleep. After two long days, we finally crossed the Kwilu River and walked up the hill to Mungindu. Tired and hungry, we were obligated to visit before being fed and provided a place to sleep.

I got up just after daybreak. Jean-Pierre was already busily getting things organized for the teacher’s conference. His anxiety was palpable despite the brave face he put on. Over sixty headmasters, and several other teachers, had walked to Mungindu for the event. The village was buzzing with expectation. But the food he had prepared for the event was delayed; it was stuck in Kikwit. Not only that, the trainers for the event had not arrived either. The only means of communicating with Kikwit was by shortwave radio, and this was more than unreliable.

I got up just after daybreak. Jean-Pierre was already busily getting things organized for the teacher’s conference. His anxiety was palpable despite the brave face he put on. Over sixty headmasters, and several other teachers, had walked to Mungindu for the event. The village was buzzing with expectation. But the food he had prepared for the event was delayed; it was stuck in Kikwit. Not only that, the trainers for the event had not arrived either. The only means of communicating with Kikwit was by shortwave radio, and this was more than unreliable.  Jean-Pierre was in the dark. The proceedings couldn’t start without supplies and food, let alone the trainers. The local church responded generously. They kicked in their support and whipped up a hundred or so servings of fufu and greens. By the time the trainers and food arrived, the sun had gone down. In the light of the full moon and with our hunger satisfied we sat down to listen to new arrivals’ harrowing stories of repairing, jimmying, pushing, waiting, searching and finally arriving in Mungindu.

Jean-Pierre was in the dark. The proceedings couldn’t start without supplies and food, let alone the trainers. The local church responded generously. They kicked in their support and whipped up a hundred or so servings of fufu and greens. By the time the trainers and food arrived, the sun had gone down. In the light of the full moon and with our hunger satisfied we sat down to listen to new arrivals’ harrowing stories of repairing, jimmying, pushing, waiting, searching and finally arriving in Mungindu.

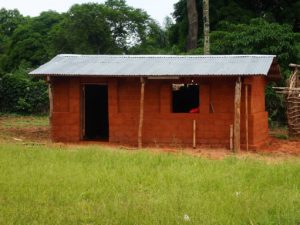

Waiting around meant I had time to visit the hospital and some of the local projects as well as get to know Jean-Pierre. I learned that the local Minister of Parliament had gotten excited about the conference and had sponsored the construction of a large classroom that could hold up to 200 people in a pinch. He purchased the tin and the wood while the parents of the students supplied the manpower. With the leftover materials, the parents and teachers constructed a two-room building to serve as a library. The doors and windows still needed to be placed but it was essentially finished. It’s amazing what even a poor rural community can pull together in two months!

Waiting around meant I had time to visit the hospital and some of the local projects as well as get to know Jean-Pierre. I learned that the local Minister of Parliament had gotten excited about the conference and had sponsored the construction of a large classroom that could hold up to 200 people in a pinch. He purchased the tin and the wood while the parents of the students supplied the manpower. With the leftover materials, the parents and teachers constructed a two-room building to serve as a library. The doors and windows still needed to be placed but it was essentially finished. It’s amazing what even a poor rural community can pull together in two months!

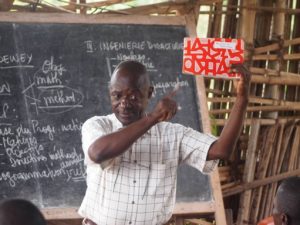

The next day the teacher’s conference began. The trainers were excellent. The elementary school trainers broke up their lectures with songs and games, techniques the teachers could use in their classrooms. The secondary school trainer carefully went through the math curriculum all the while interacting with and engaging his listeners. He told me later that he had spent several years in France completing his masters before coming back to Kikwit to teach at the university. Mike, for his part, observed, interviewed teachers on camera, and experimented with technology. He had brought with him e-books and videos on a Kindle pad.

The next day the teacher’s conference began. The trainers were excellent. The elementary school trainers broke up their lectures with songs and games, techniques the teachers could use in their classrooms. The secondary school trainer carefully went through the math curriculum all the while interacting with and engaging his listeners. He told me later that he had spent several years in France completing his masters before coming back to Kikwit to teach at the university. Mike, for his part, observed, interviewed teachers on camera, and experimented with technology. He had brought with him e-books and videos on a Kindle pad.

Unfortunately, I had to leave the next day. I left Mike behind. As expected, the rented vehicle broke down on the way back to Kikwit. But as I sat there in the hot sun waiting for the chauffeur to tie the wheel back onto the axle with a piece of rope, I reflected on my experience. What had my contribution been here? Mungindu is a typical poor Congolese community, yet they found resources in their red clay to make bricks, money from a local official for wood and tin, hard work from parents, local cooks with access to local food through the church, teaching expertise from a nearby urban center, and a group of headmasters that were hungry to learn.

Unfortunately, I had to leave the next day. I left Mike behind. As expected, the rented vehicle broke down on the way back to Kikwit. But as I sat there in the hot sun waiting for the chauffeur to tie the wheel back onto the axle with a piece of rope, I reflected on my experience. What had my contribution been here? Mungindu is a typical poor Congolese community, yet they found resources in their red clay to make bricks, money from a local official for wood and tin, hard work from parents, local cooks with access to local food through the church, teaching expertise from a nearby urban center, and a group of headmasters that were hungry to learn.

What then is the question we should be asking? No doubt, the poor need money and resources. And we, the non-poor, have a responsibility to contribute. But more importantly, they need hope and encouragement. They need to see that solutions are essentially already there, within their own communities. Local initiative and drive are indispensable. They are more important than the resources a white foreigner, like me or Mike, can bring. Every community has assets and these assets are the essential building blocks for community transformation. The question then is not, “What do you need?” but rather, “What do you have?”

About the author

Murray Nickel, MD, is President of International Mennonite Health Association (IMHA) and an emergency physician living in Abbotsford, British Columbia, just outside of Vancouver. He spent six years in Congo in association with Mennonite Brethren Mission and now travels back and forth between Congo and Canada two or three times a year. He has a special interest in human development and transformation in the context of the poverty.

Murray Nickel, MD, is President of International Mennonite Health Association (IMHA) and an emergency physician living in Abbotsford, British Columbia, just outside of Vancouver. He spent six years in Congo in association with Mennonite Brethren Mission and now travels back and forth between Congo and Canada two or three times a year. He has a special interest in human development and transformation in the context of the poverty.