Mennonite Health Journal

Articles on the intersection of faith and health

Ebola

R. Michael Massanari

from Mennonite Health Journal, Vol. 16, No. 4 – November 2014

[Author’s note: This manuscript was prepared as a brief synopsis of the current Ebola epidemic. Space does not permit an elaboration of current protocols for managing exposures, patients, and transmission. CDC websites with pertinent up-to-date information are provided for the interested reader. It is important to recognize that recommendations for managing the epidemic are changing rapidly as experts acquire new knowledge in the course of the epidemic.]

Thus week by week the prisoners of plague put up what fight they could. …by this time the plague had swallowed up everything and everyone… (There was) only a collective destiny made of plague and the emotions shared by all. Strongest of these emotions was the sense of exile and desperation…. The Plague, Albert Camus

From time to time diseases emerge that are shrouded in mystery and threaten the well-being, indeed survival, of large segments of the population. Usually manifest as epidemics of infectious diseases, it is a lack of knowledge about the etiologic agent, its source, the mode of transmission, and effective management that amplifies fear and irrational responses to the outbreak, emotions that are compounded when healthcare workers are threatened in the course of the epidemic. Despite the scientific advances and technological sophistication of contemporary medicine, these epidemics continue to confound and challenge those who provide care. We need but recall influenza, Legionnaire’s Disease, HIV/AIDS, SARS, and now Ebola among recent epidemics that serve as reminders that modern medicine is not invincible.

What is Ebola? Does it pose a significant threat, particularly to us who are healthcare providers? What can be done to prevent its spread and to manage those who have contracted the disease?

What is Ebola? Does it pose a significant threat, particularly to us who are healthcare providers? What can be done to prevent its spread and to manage those who have contracted the disease?

The Agent. The Ebola River is located in the Democratic Republic of Congo. It was along this river that the first outbreak of the disease that now carries its name was identified in 1976 and where a Belgian physician, Dr. Peter Piot, isolated the virus that caused the disease.

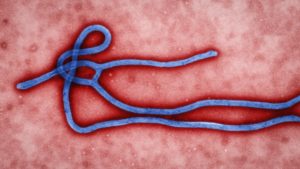

Five distinct Ebolaviruses (family Filoviridae, genus Ebolavirus) have been isolated, four of which are known to cause human disease. Recent evidence suggests that bats in several African countries serve as reservoirs for Ebolaviruses; however, it is uncertain how the virus is maintained in that species. The Ebolaviruses cause periodic epizootics in non-human primates. Humans probably contract the infection from bats or other wild mammals following which it is readily spread to close human contacts thereby initiating an epidemic. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014) (http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/resources/virus-ecology.html)

Clinical Disease. Ebola is a rare, acute, and deadly infection. Clinical disease is typically manifest by abrupt onset of fever that occurs 8-12 days following exposure to an infected patient. Other symptoms may include chills, malaise, muscle pain, and loss of appetite. Because these symptoms are non-specific they may be confused with other infections, particularly where and when the disease is unsuspected.

In West Africa, site of the current epidemic, other tropical diseases must be considered, including malaria, typhoid fever, and pneumonia. As the disease progresses over the next five days patients may experience gastrointestinal symptoms including severe watery diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Other symptoms include chest pain, shortness of breath, headache, and confusion. Evolving clinical signs include conjunctivitis, seizures, cerebral edema, and an erythematous maculo-papular rash over the neck, arms and trunk. Frank hemorrhage is unusual; however, petechiae, ecchymosis, mucosal bleeding, and bloody diarrhea may occur later in the disease course.

The more severe the symptoms and signs of the disease, the more likely the patient will die of the disease, usually between days 6-16 of the infection. Death usually results from multi-organ system failure or/and septic shock. Patients who survive generally have milder disease with resolution of fever around day six. However, survivors may experience a prolonged convalescence. The case fatality rate among documented cases in West Africa has ranged between 69-72%.

Pathogenesis. Ebola virus enters the host through mucus membranes, breaks in the skin, or in the case of health workers parenteral exposure via accidental needle sticks. The virus is particularly virulent, infecting an array of human cells, spreading rapidly to local lymph nodes and then to the liver, spleen, and the adrenal cortex. Liver involvement is associated with abnormal clotting while adrenal cell death is associated with reduced steroid synthesis and hypotension.

Although survivors generate an effective immunological response to the virus, it appears that the virulence of the agent is such that in fatal cases it overwhelms the host before the patient is able to generate an effective defense against the infection. Early laboratory abnormalities include reduced white blood cell and platelet levels. Striking elevations in hepatic and pancreatic enzymes are associated with cellular necrosis while abnormal coagulation tests signal disseminated intravascular coagulation. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014) (http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/clinician-information-us-healthcare-settings.html)

Diagnosis. Several laboratory diagnostic tests are available to confirm the diagnosis following onset of symptoms and include ELISA testing, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and virus isolation. Later in the course of disease, testing for IgM and IgG antibodies to Ebola virus can be used to confirm the diagnosis. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014) (http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/diagnosis/index.html).

Because of the risk of transmission to health workers and laboratory personnel during specimen collection and processing, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has offered explicit guidelines for specimen handling. This brief overview of Ebola does not permit elaboration of these protocols. For more information the reader should refer to the following website: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/interim-guidance-specimen-collection-submission-patients-suspected-infection-ebola.html. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014)

Treatment. At the time of this writing, novel therapeutic interventions utilizing molecular knowledge regarding viral pathogenesis and host immunological responses are being investigated. However, current therapeutic recommendations rely primarily on symptom management and management of organ system dysfunction.

The critical importance of supportive care should not be underestimated. Recent observations from experts providing services in Africa suggest that excellent supportive care might significantly reduce case mortality rates because many patients die from lack of access to parenteral hydration when diarrhea and vomiting cannot be controlled. In addition to hydration, attention to proper oxygenation and management of associated infections is important. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014) (http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/treatment/index.html)

Controlling Transmission of Ebola. The uncontrolled epidemic of Ebola in West Africa, the high case mortality rates, the lack of effective therapy, the risk of transmission to health workers, and more recently identification of isolated cases in the United States and Europe have sounded alarms around the world. To be sure Ebola is a disease with which to reckon. However, it is primarily persons in close contact with the patient and health workers that are at risk of contracting Ebola.

The infection is transmitted by direct exposure to the patient’s blood or body fluids (i.e. mucus, urine, feces, sweat, semen, emesis, breast milk). Ebola is not spread via water, food, or airborne transmission. In Africa, exposure may also include contact with wild animals.

The good news is that access to appropriate equipment that provides protective barriers between the infected patient and contacts, along with proper disposal and sterilization of medical equipment will afford safe protection and prevent transmission. The bad news is that (i) contacts, including health workers, fail to suspect that the patient might be infected with Ebola; and (ii) contacts, including health workers, lack access to or fail to properly use effective barrier equipment to prevent spread of infection.

This brief synopsis of the Ebola epidemic does not permit a detailed elaboration of the protocols for managing persons exposed to and patients with Ebola infection. Perhaps the most important take-away messages for health workers who read this article are:

- Raise your level of suspicion. Certainly, most patients with fever who seek acute care will neither be exposed to or have Ebola infection. However, in the event of unexplained fever and other symptoms suggestive of Ebola, be certain to include in your history queries regarding travel and/or exposure to travelers from Africa or to people who may have been infected with Ebola virus.

- Implement contact and droplet precautions. Refresh your knowledge regarding contact and droplet precautions, where to access appropriate protective barrier equipment, and how to appropriately don and discard the equipment should you encounter a person reporting possible exposure.

- Report immediately to Public Health Authorities. In the event you encounter a person who might have been exposed to Ebola virus infection, report immediately to the institutional infection control officer, to the local and state public health departments, and to the CDC (CDC’s Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100). (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014) (http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/eoc.htm)

For more information regarding monitoring and management of persons exposed to Ebola virus infection, see Interim U.S. Guidance for Monitoring and Movement of Persons with Potential Ebola Virus Exposure: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/monitoring-and-movement-of-persons-with-exposure.html).

For more information regarding safe management of patients diagnosed with Ebola infection, see Safe Management of Patients with Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) in U.S. Hospitals: (http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/patient-management-us-hospitals.html).

For more information regarding infection control protocols for managing patients with Ebola infection, see Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Hospitalized Patients with Known or Suspected Ebola Virus Disease in U.S. Hospitals: (http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/infection-prevention-and-control-recommendations.html).

While it is unlikely that any of us as health workers will encounter persons exposed to or infected with Ebola virus, the threats associated with the current epidemic make it imperative that we avoid complacency and that we maintain vigilance and knowledge regarding appropriate and effective protocols for managing these encounters. Confronted with caring for patients with Ebola infection, we need not be overwhelmed by emotions of fear and despair, but rather render care with compassion and confidence that we can do so while protecting ourselves and those around us.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, January 10). CDC Emergency Operations Center (EOC). Retrieved from Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response: http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/eoc.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, November 5). Diagnosis. Retrieved from Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease): http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/diagnosis/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, November 6). Ebola virus disease Information for Clinicians in U.S. Healthcare Settings. Retrieved from Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease): http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/clinician-information-us-healthcare-settings.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, October 20). Interim Guidance for Specimen Collection, Transport, Testing, and Submission for Persons Under Investigation for Ebola Virus Disease in the United States. Retrieved from Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease): http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/interim-guidance-specimen-collection-submission-patients-suspected-infection-ebola.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, November 5). Treatment. Retrieved from Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease): http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/treatment/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, August 1). Virus Ecology Graphic. Retrieved from Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease): http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/resources/virus-ecology.html

About the author

Michael Massanari, MD MS FACP, is a retired physician and professor of medicine whose sub-specialty training included infectious diseases and epidemiology. Mike and his wife, Lois, currently live near Bellingham, Washington where their daughter Analisa and family reside. Although not currently attending a Mennonite Church, they maintain their lifelong ties with the church through their son Eric who is a Pastor and Chaplain with the Mennonite Church in Newton, Kansas. In addition to caring for grandchildren, they enjoy birding, traveling, reading, and participation in church and community choirs.

Michael Massanari, MD MS FACP, is a retired physician and professor of medicine whose sub-specialty training included infectious diseases and epidemiology. Mike and his wife, Lois, currently live near Bellingham, Washington where their daughter Analisa and family reside. Although not currently attending a Mennonite Church, they maintain their lifelong ties with the church through their son Eric who is a Pastor and Chaplain with the Mennonite Church in Newton, Kansas. In addition to caring for grandchildren, they enjoy birding, traveling, reading, and participation in church and community choirs.